Dragon Quest (and Final Fantasy) Retrospective: Benford’s Law and the Experience Curve

In 1881, as the story goes, an astronomer named Simon Newcomb was flipping through a book of logarithm tables – this was before you had access to this information at your fingertips with scientific calculators or a computer and still had to do all of your math by hand – and he noted that the earlier pages were much more worn than the later pages, as if the information on the earlier pages was needed more often than the information contained in the later pages of the book. This typically isn’t the case with other kinds of textbooks, just with logarithm tables, suggesting that there was some co-relation between the frequency of certain digits at the start of a number and the amount of times those numbers were referenced. Basically, the lower the digit, the more often that digit would be found at the start of any naturally occurring number.

The phenomenon would again be observed, this time in 1938 by Frank Benford, for whom the law is named (some scholars attempt to correct this by calling it the Newcomb-Benford Law). He went further than Newcomb did by testing the observation with several different data sets and confirming that it is true. It turns out that if you take something like US populations, 30.1% of them will contain the number 1 as its first digit. The frequency of the number 2 at the beginning of a number drops to 17.6%. And if you follow this all the way to the number 9, it appears at the beginning of a number only 4.6%. This sounds almost paradoxical in a world that would appear to be completely random, but it turns out that the world is less random than one would think.

In my estimation, the discovery of Benford’s Law is the modern day equivalent of Archimedes in the bathtub. Benford’s Law continues to have new and interesting applications, even today. None of us are actually supposed to know that it can be used to detect tax fraud, so I won’t bother mentioning it here. What I can say is that it has recently been used to detect bot accounts on Twitter and is likely the reason that we know about the Russian bot network that the far right in the United States dismisses as fake news. In fact, the law has so many neat applications that I’d like to apply it to something I’ve observed during the course of my time writing about Final Fantasy and Dragon Quest on the NES.

“It also helps that experience curves, while still steep, are based on specific algorithms now and not arbitrarily calculated by the developers. Gone are levels which require an even number of experience points and which seem to increase that requirement in an arbitrary manner.” -from the Dragon Quest III Retrospective

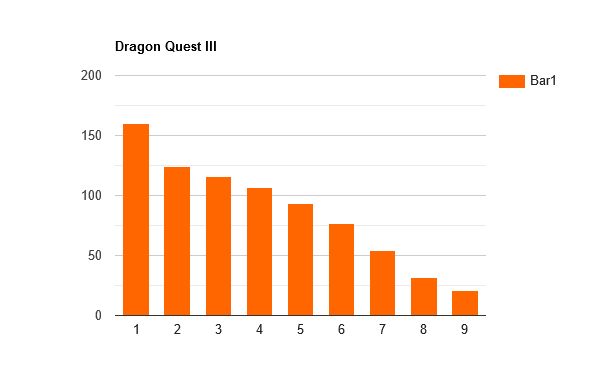

When writing my retrospective articles, I claimed that the character progression systems in the first two Dragon Quest games were artificially constructed, right down to the experience points needed per level, and then starting with Dragon Quest III, the amount of experience points required per level was handled by an actual algorithm. Other than most of the experience values being in multiples of 1000 in the first two games versus the more random-looking numbers present in the third, there is another way to tell which experience curves aren’t natural. If Benford’s Law holds true, about 30% of the numbers involved should begin with a 1 in Dragon Quest III.

Rather than leveling up all the characters to 99 and gathering the data that way, I simply used the tables provided at Mike’s RPG Center for my data on the first three Dragon Quest games.

The best thing, in my opinion, of the Dragon Quest series when it comes to gathering data for these graphs is that since each character has their own separate experience table, there’s plenty of data to use. Looking at Dragon Quest III, it does follow the phenomenon that Newcomb and Benford observed. The number one shows up as the first digit so many more times than the rest of the digits, and the number nine so few times, but in my calculations, a one shows up only about 20% of the time. That said, it still appears the most, as the following graph shows:

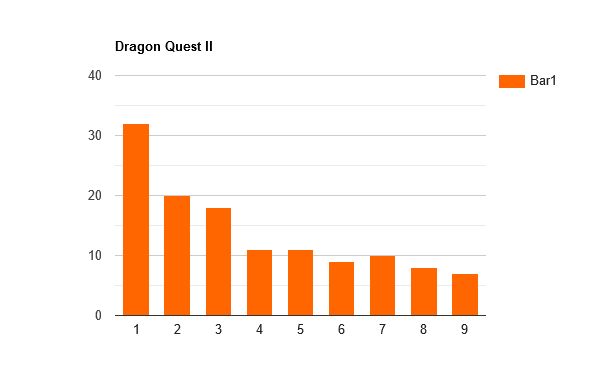

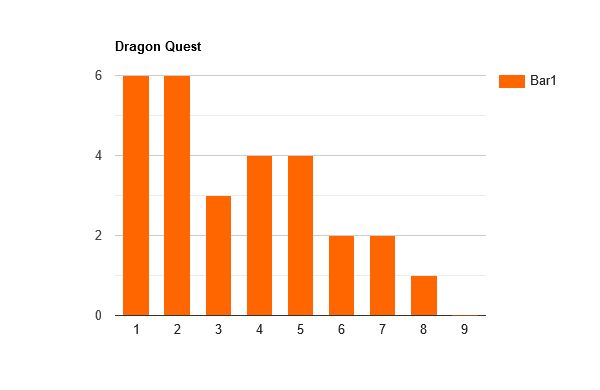

There doesn’t seem to be enough data on experience required to level in the first two Dragon Quest games, considering there are only three characters in the second game and they each have a relatively low level cap, and there’s one character in the first game with a level cap of 30. Even with those limitations, it seems as if some compliance to Benford’s Law is observed, as if the games’ experience tables weren’t just built by hand.

Given the odd spurts of growth and plateaus seen in the two games, I would therefore conclude that a more natural experience curve was first constructed before it was massaged a little by the developers, smoothed out in places to make leveling a bit easier. That sort of explains the odd decision to make the Prince of Cannock’s progression from level 28 to level 45 require, in order: 30 thousand, 40 thousand, 30 thousand, another 30 thousand, 40 thousand, 50 thousand, 50 thousand, 40 thousand, 60 thousand, 60 thousand, 60 thousand, 60 thousand, 60 thousand, 20 thousand, 60 thousand, 60 thousand, and finally 40 thousand. The Princess of Moonbrooke had her experience table massaged a little as well, but the graph above suggests that the curve began naturally.

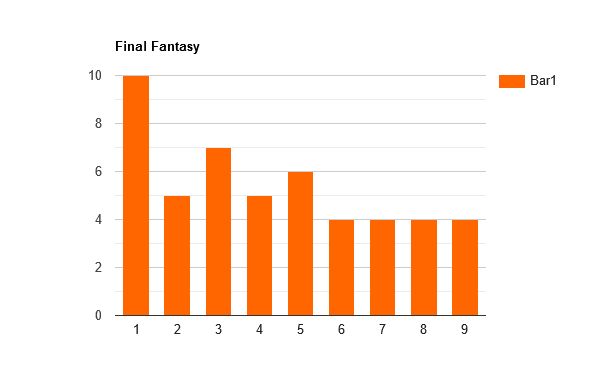

Unfortunately, Final Fantasy typically uses one experience curve for all characters, which makes gathering enough data to check it against Benford’s Law a little tough. With only 49 data points, the graph for the first Final Fantasy game looks like this:

The only digit that stands out in the game is the one, which makes it seem like the game would conform to Benford’s Law if we had more data to look at. I wasn’t able to find the data for Final Fantasy III‘s required experience points in time for this article and I didn’t want to have to grind all 99 levels, but even if I did, there’d only be 98 data points and I wouldn’t be able to conclude anything concrete about Benford’s Law.

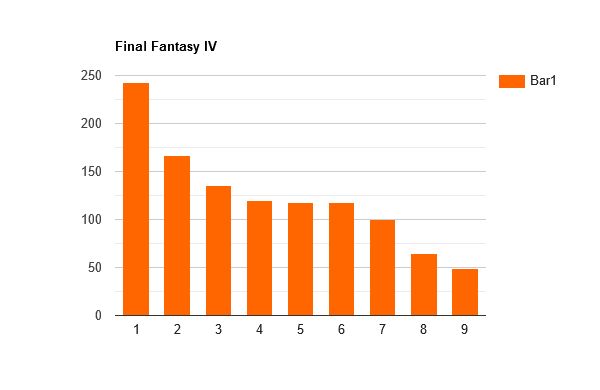

Final Fantasy IV is unique to the series in that each character levels up with their own separate experience curve, just like a Dragon Quest game. As far as I can tell, no other game in the series did that, and it’s because of this that we can collect a ton of data to come up with a great bar graph for the game. Not only that, but there’s a site that compiled a ton of information about the game called the Final Fantasy 4 Reference Book, and it’s there that I found the data required for the following graph:

An interesting thing to know about the game is that the experience required for each character begins as a curve but then around level 70, the curve smooths out for each character. Since a character’s stat growth is pre-determined up to that point, upon which it randomizes and stats can potentially go down, it feels like the developers only intended for characters to fight the final boss around level 70 and no higher. Players are literally risking being punished for grinding any further than that.

The arithmetical straightening of the curve at level 70 is one of two flaws to the Final Fantasy IV data. The other is that, despite the number of characters I can draw data from, several of them begin already leveled up a bit. Cecil and Kain both start the game at level 10 and meet up with Tellah at level 20. The one with the least amount of data is FuSoYa, who joins at level 50 and requires so much experience to level, by the time he leaves the party, the only stat of his that’ll have grown is his HP unless players go out of their way to make him stronger for no real reason other than they want to. Unfortunately, that skews the data a little and although it looks like a standard Benford’s Law graph, the middle part definitely reflects the uniform way characters level up past 70. Still, the bars do follow a rough estimation of Benford’s Law. It should be noted that there was an equal amount of numbers beginning with a 5 and a 6, and there were only two more numbers beginning with a 4 out of the entire list of numbers used.

In writing this article, I hope that I have illustrated the odd observations about the world of numbers that Benford’s Law tries to explain. I have also partially disproven my own assertion that the experience curve in the first two games are unnatural. They seem to have been rounded and massaged somewhat, but there is a hint of a natural curve to the experience gains in those first two RPGs.