Dragon Quest Retrospective – Dragon Quest

For RPG fans, this is a strange time. In the past, there has always been a new, numbered Final Fantasy game both announced and in production, but currently there is not. Kingdom Hearts has finally reached a point where all the confirmed games have come out and naught but a mobile title is currently in development, with no word on when the next story significant game is going to be made. The Dragon Quest series has released an eleventh numbered game recently and although development has said to have begun on the next, we’re likely years before number twelve comes out. The first part of the Final Fantasy VII remake has also been released, but the next part hasn’t been announced yet. Now, during a gap of time where nothing new is coming out and nothing new has been announced, seems like the best time to look back at Square-Enix’s three flagship titles and find out what makes them so great, what might’ve held some of them back, and analyze how they developed over time.

The company which would become Square-Enix was once two competing companies, Enix and Squaresoft. At the earliest point in the histories of Dragon Quest and Final Fantasy, neither company could consider the other to be direct competition, not yet. The release of Dragon Quest occurred before Square was even founded, although a form of it did exist as part of the Den-Yu-Sha construction company about three years prior. The release of the first Kingdom Hearts game is interesting too, for it was developed and released in Japan during a time when the two companies were still separate but negotiating a merger. By the time the game was released in North America, the two companies were now one. In a way, Dragon Quest was always an Enix game, Final Fantasy was always a Squaresoft game and to the North American audience, Kingdom Hearts was always a Square-Enix game.

It should be noted that, prior to Final Fantasy, Squaresoft had developed and published RPGs to varying degrees of success. Enix and their main developer Chunsoft developed Dragon Quest as their first RPG completely from scratch, although Enix had published other RPGs to the home computer market before then, so neither company were fully new to the genre when they created what would become their most famous pieces of software.

The Japanese public took to Dragon Quest like a child takes to candy. The first game sold enough to justify developing and publishing three sequels in quick succession, all for the NES, and another game for the SNES soon after. The Dragon Quest series would start to slow down and pace itself at this point, going from four original titles for the NES to two for the SNES and one for the PlayStation (not counting spin-offs that were developed and published during this time), but Enix would go on to publish many other well loved games like the Soul Blazer series, the Star Ocean series, Valkyrie Profile, and so on.

Music is an important component of both Dragon Quest and Final Fantasy, and is likely the first thing a player will notice at the start of a game. I don’t think I’m exaggerating when I say that one of the most iconic aspects of Dragon Quest, both as a game and as a series, are the compositions by Koichi Sugiyama. He is the exclusive composer of Dragon Quest soundtracks, including spin-off titles such Torneko: The Last Hope and Dragon Quest Monsters.

Before I go any further, and just so I don’t have to mention this in every retrospective article, yes, he’s a garbage person with regressive views towards history and women. This is not the time and place for that discussion. I’m sure that, if the Dragon Quest series was developed in this day and age, Koichi Sugiyama might not have been selected to compose for it, but his composition style has become so indelibly linked to the overall feel of the series that when I think of Dragon Quest, it’s hard not to think of the iconic fanfare that plays at the beginning of nearly every game.

While Final Fantasy would use a simple arpeggio to introduce players to its worlds, Dragon Quest went with a full fanfare, introducing players in as bombastic a manner as possible to the game which they were about to experience. It’s almost arrogant in a way. Final Fantasy‘s arpeggio calmly and humbly invites players into the world they’re about to explore, but Dragon Quest announces from the rooftops that the game is ready to begin. “Are you ready for an adventure?” the fanfare asks. “Because this is going to be the grandest adventure of your life.”

Granted, it doesn’t sound all that grand as an 8-bit chiptune, not in its original form. It loops in such a way that players familiar with the full piece will find it a bit odd to hear only half of the song. It’s like listening to Final Fantasy II’s version of the chocobo theme and expecting it to continue on rather than loop right away. The first game to open with the full fanfare was Dragon Quest IV.

Speaking of missing iconic themes, the game also features a start menu theme that differs from the one made famous later in the series. For some reason, Sugiyama composed original start menu themes for the first three games and then carried over the third game’s theme in every game since. The third game’s extreme popularity in Japan might have a lot to do with that.

In a way, the entire first soundtrack is iconic. I know I’m overusing that term to near Ubisoft levels, but it really is. Many of the tunes are instantly recognizable and Sugiyama’s Dragon Quest style was not yet fully developed when he composed for the first game. The tunes are simple and easy to follow and don’t get in the way of the game at all. Even the fanfare at the beginning is toned down somewhat, as if Sugiyama was testing the waters and seeing what the NES sound chip was capable of. He had a vision of how he wanted his compositions to sound and he likely needed more time than he had to make it sound exactly how he could hear it in his head.

One could consider Dragon Quest to be an experiment on Enix’s part, for it was the first time a game quite like it had been released. That said, Enix came out swinging for the fences. As stated before, Squaresoft had not formally entered the market at this point. There was no rivalry between the two companies when Dragon Quest was released, and this was not the opening salvo in a battle of juggernauts. This was a company wanting to release a game they worked hard on and believed was good.

An interesting thing about the design of the game is that Dragon Quest is meant to be played in a very specific manner. Although the world is open and free to be explored, it is generally a bad idea to cross bridges and enter territory within which the lone warrior in the game is incapable of surviving. The way it’s supposed to work is that enemies on the other side of bridges are stronger than enemies the warrior had been fighting before. In practice, sometimes the area a monster’s supposed to appear in overlaps with a portion of the land on the wrong side of the bridge. This usually doesn’t become an issue in casual play, but when one is grinding for levels before they feel comfortable in the next area and one encounters the stronger enemies before one feels ready on multiple occasions, this is something they tend to notice.

The lands surrounding Tantegel Castle are a great place to learn not to bite off more than you can chew, for venturing too far into ghost territory can be just as bad as crossing a bridge until the warrior is at least level three and has purchased some half decent equipment from the shop in Brecconary.

This lone warrior finds himself funneled along to very specific towns as he gains power, fighting to earn money to upgrade his gear and by the time he can afford it, he’s also generally strong enough to make it to the next town and repeat the process. Eventually, he’s strong enough to go into the castle of the Dragonlord and defeat the light’s mortal enemy. Or accept his offer, both endings are canon now, with the bad ending splitting off into an alternate universe where players save the world by playing Minecraft a bit.

This lone warrior finds himself funneled along to very specific towns as he gains power, fighting to earn money to upgrade his gear and by the time he can afford it, he’s also generally strong enough to make it to the next town and repeat the process. Eventually, he’s strong enough to go into the castle of the Dragonlord and defeat the light’s mortal enemy. Or accept his offer, both endings are canon now, with the bad ending splitting off into an alternate universe where players save the world by playing Minecraft a bit.

I don’t know if it was known at the time how important specific character names were going to be in the Dragon Quest series, so it’s interesting to note that in the first game, your name is your power. The game is programmed in such a way that a player’s name determines the warrior’s starting stats and the stats he gains throughout the game. It also turns out, but I won’t say why at this point in this retrospective series, that one particular name carries with it incredible significance, and that name is Erdrick. It is a name that will come back several times throughout the series.

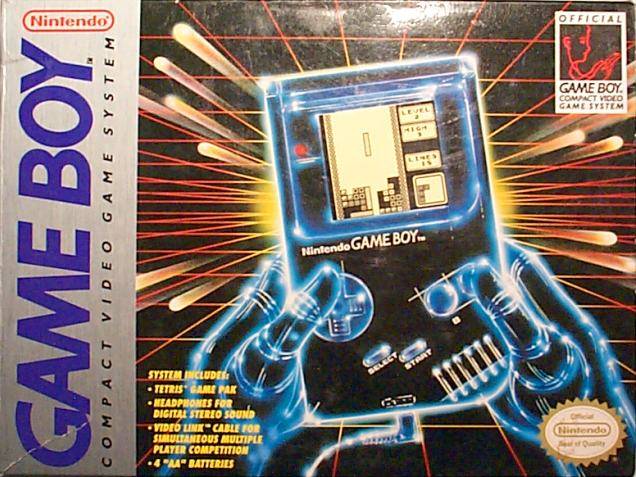

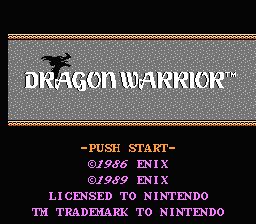

A note about names: for the most part, I’m going to stick with North American naming when it comes to the characters, place names and spells in each game. As is also the case with Final Fantasy, not everything was translated faithfully from the beginning. Fire3 in Final Fantasy IV would later become Firaga, for example. And in Dragon Quest, the hero Erdrick was known as Loto in Japan. Throughout both the Final Fantasy and Dragon Quest retrospectives, I’ll be using names seemingly arbitrarily, depending on the games and their translations. I also will not be playing every single version of each game and won’t go into too much detail about the differences between them all, although I’ll make exceptions along the way if they’re significant. Plus, the version of each game I’ll be playing will not always be the best version to play. I am talking about the NES version of Dragon Quest here, whereas the SNES and Game Boy versions of the game are seen by many fans as superior.

That said, I’m going to refer to the series as Dragon Quest whenever possible, even though the game I played was actually called Dragon Warrior in North America at the time.

It’s admirable that when the Dragon Quest games were localized into English, the naming conventions from the first games were carried over, even after fans learned of the name changes. The name of Erdrick continued to be used as recently as Dragon Quest XI. Even the Final Fantasy localization teams kept the character’s English name when making references to Dragon Quest, and that’s a series that’s often unwilling to let translation errors stand regarding the names of its characters.

Dragon Quest‘s story is very basic, and only really serves to justify the gameplay. The princess has been kidnapped and it’s up to the player to both rescue the princess and defeat the Dragonlord. The Dragonlord’s motives aren’t known other than a vague notion of ruling the world, and is likely the kind of story that one would come up with as their first Dungeon’s and Dragons adventure. Go and rescue the princess. Now go and defeat the Dragonlord. Done. It’s not a very deep plot, as plots go, but at the time it didn’t need to be. Criticizing Dragon Quest‘s plot is like criticizing an elementary school’s art class.

Dragon Quest‘s story is very basic, and only really serves to justify the gameplay. The princess has been kidnapped and it’s up to the player to both rescue the princess and defeat the Dragonlord. The Dragonlord’s motives aren’t known other than a vague notion of ruling the world, and is likely the kind of story that one would come up with as their first Dungeon’s and Dragons adventure. Go and rescue the princess. Now go and defeat the Dragonlord. Done. It’s not a very deep plot, as plots go, but at the time it didn’t need to be. Criticizing Dragon Quest‘s plot is like criticizing an elementary school’s art class.

Instead, 99% of the game involves fighting enemies one at a time and gaining power enough to defeat the Dragonlord with. The game is relatively short compared to more modern Dragon Quest titles – twenty hours or less as opposed to the eighty to a hundred hours players are reporting it took them to beat the eleventh game – but each level of power gained still represents a decent chunk of time investment. At first, the levels come quickly, as is smart in game design. You want to get players hooked, so the first level up requires less than ten experience points and takes about three or so minutes to acquire. The next level up takes up to eight minutes, including stops at the inn. At this point, it’s clear that the warrior is only afforded enough time between stops at the inn to earn enough money to offset his inn costs.

It is upon reaching level three that the game gets a little easier. The experience curve is sharp, but level four only takes another nine minutes to achieve and then the next couple level ups take twelve and fifteen minutes. Keep in mind that the warrior is upgrading his equipment when he can and fighting as tough an enemy as he can handle. Magicians which could’ve wiped the floor with him at level four are much more manageable at level six.

Players notice right away that they are getting stronger, too. The numbers in the first hour of the game are so low that it soon becomes apparent that slimes, which were a major threat before gaining those first experience points, are no longer a threat by level three and actually begin running away in fear by level four or five. At this point, the more cautious of players will see not only the diminishing returns of having to fight more and more slimes per level, but many of the slimes will be running away entirely and thus their progress will be halted until they venture out into Ghost and Drakee and Magician territory.

Before going any further, let’s talk about Tantegel castle. When starting the game, the door is locked and there’s no way to get out. You pretty much have to talk to the king if you want to know what’s up. Then you’re told to take what’s in the treasure chests. In them are: a torch, 120 gold pieces and a key. The key is for unlocking doors and is consumable upon use, with this particular key being used to get out of the room. The torch is also consumable and is intended for the first cave which is within walking distance of the castle and doesn’t contain any enemies, just a tablet with further instructions for the player. The gold pieces are for buying equipment, but it’s not enough to buy everything. The equipment shop in the nearby town of Brecconary requires a lot more than 120 gold pieces to buy everything. It is here that the game teaches players that they’re not getting a lot of things for free, they’re going to have to earn pretty much everything if they want to make it through the game.

Before going any further, let’s talk about Tantegel castle. When starting the game, the door is locked and there’s no way to get out. You pretty much have to talk to the king if you want to know what’s up. Then you’re told to take what’s in the treasure chests. In them are: a torch, 120 gold pieces and a key. The key is for unlocking doors and is consumable upon use, with this particular key being used to get out of the room. The torch is also consumable and is intended for the first cave which is within walking distance of the castle and doesn’t contain any enemies, just a tablet with further instructions for the player. The gold pieces are for buying equipment, but it’s not enough to buy everything. The equipment shop in the nearby town of Brecconary requires a lot more than 120 gold pieces to buy everything. It is here that the game teaches players that they’re not getting a lot of things for free, they’re going to have to earn pretty much everything if they want to make it through the game.

The game also doesn’t make it easy. As mentioned before, the first few stays at the inn are going to use up the gold pieces earned from fighting slimes, making it quite the struggle to even get to level two, but then at level two, there’s a slightly higher HP cushion, which should help players get the experience necessary to climb further to level three. Once there, players will find it easier, both due to extra strength, HP and the Heal spell, to not only get to the next level but to also start actually accumulating money.

Most of the game is this, and if you really think about it, Dragon Quest describes pretty much every game in the genre. Players must level up, seek enemies that drop more gold and more experience points and try to be powerful enough for the challenges ahead. All NPCs must be talked to in order to figure out where to go, equipment shops must be visited, and so on. It’s not that complex of a game, but then it doesn’t need to be. With how small the game is, it can be perfectly balanced for where the developers want their players to be at all times. There is still somewhat of an element of luck, given that excellent moves can happen, which are the game’s version of critical hits and which aren’t determined by any of the warrior’s stats. Attacks can also sometimes miss through no fault of the player and again, this is not determined by stats at all, just by an arbitrary random number the game generates.

Later levels come after much more time investment. Level seven can take almost a half an hour to acquire, as does level eight. Level twelve can take almost three quarters of an hour of solid fighting, and level fifteen represents one full hour. All the while, money keeps flowing in, enough to spend on gear upgrades. However, when I purchased the last and most expensive piece of protective armour, my warrior named CW was level thirteen and still wasn’t powerful enough to make headway into the next part of the game, so at that point a lot more grinding was needed.

Dragon Quest‘s balance leans more towards lengthy grinding and the rewarding of hard work, but I feel like the game was also balanced with trial and error in mind. Players are supposed to get in over their heads, die a few times and pick themselves back up. This is evident in the way that occasionally at random, CW missed the enemy two or three times in a row, or when CW was put to sleep for several turns at a time. The game’s lone warrior is supposed to be defeated occasionally, and this hypothesis is supported by the fact that the game has no Game Over screen. Instead of sending players back to the title screen, players find themselves at Tantegel Castle with half their gold missing, and it’s always half. Die with 4 gold pieces, and death carries with it a 2 gold piece penalty, but die with 40000 gold pieces and death cripples the player with a hefty 20000 gold piece fine.

Tantegel Castle also serves as the game’s sole save point. Talking to the king will record your adventure in the Imperial Scrolls of Honor. The world of Alefgard is small enough that this doesn’t feel like much of an imposition, especially with there being no risk to death other than to your wallet.

It’s not like anyone needs that money anyway. After making it to Cantlin and buying what’s there, money is pretty much useless and does nothing but accumulate. Before players get there, and if they know what they’re doing and don’t die along the way, then by the time the Magic Armor is purchased and the player can try to get to Cantlin, they’ll be several levels below where they should be and they’ll lack Healmore, which is pretty much required to get to Cantlin. Unfortunately, this means several more hours of grinding are needed in order to learn the spell.

It’s for this reason that I also wonder what the purpose of the Goldman is. It’s a golem made of gold and although it awards only 6 experience points, it can drop almost 200 gold pieces at a time. Presumably this is to help save up for the last few pieces of gear, but beyond that it sucks for grinding levels with. It requires more time to beat than other enemies in the same area and drops much less experience. It is also a common enemy during the level grind between Rimuldar and Cantlin.

It’s for this reason that I also wonder what the purpose of the Goldman is. It’s a golem made of gold and although it awards only 6 experience points, it can drop almost 200 gold pieces at a time. Presumably this is to help save up for the last few pieces of gear, but beyond that it sucks for grinding levels with. It requires more time to beat than other enemies in the same area and drops much less experience. It is also a common enemy during the level grind between Rimuldar and Cantlin.

Overall, this seems to indicate that Dragon Quest may have been balanced towards being played in a trial and error manner, but the downside to that is that it can get overly grindy for players who already know what to expect. While this may be acceptable in Japan, this is considered terrible game design in North America, and is likely one of the biggest reasons Dragon Quest has struggled to find an audience here. The notion that players will run up against a wall and the only cure is to grind for several hours on the same enemies over and over in a game that’s already short and for no reward other than the ability to stop dying in the next area is absurd, especially by today’s standards. Players are typically turned off by the idea that they’ll have to just sit there and grind for money in order to buy gear and then grind for experience in order to get to the next gear shop when games like Final Fantasy are generally balanced to allow for players to buy what they need as soon as they reach a new area and generally be powerful enough to immediately move forward from there.

Interestingly, after reaching level fifteen, the game’s experience curve begins to plateau. The next few levels require three thousand experience points each, and then level seventeen increases that requirement to four thousand points each. It’s a kind of mercy that the developers afforded the player, for it helps them determine how much grinding they have ahead of themselves if they want to reach a certain level of power. Healmore is finally earned during this grind and thus the trek to Cantlin can begin in earnest.

Interestingly, after reaching level fifteen, the game’s experience curve begins to plateau. The next few levels require three thousand experience points each, and then level seventeen increases that requirement to four thousand points each. It’s a kind of mercy that the developers afforded the player, for it helps them determine how much grinding they have ahead of themselves if they want to reach a certain level of power. Healmore is finally earned during this grind and thus the trek to Cantlin can begin in earnest.

While playing classic NES RPGs like this game, I go back and forth regarding whether the game is actually kind of well made or if it isn’t. I think the notion that it isn’t comes from wanting to rush through the game and feeling like I’m being held back by things like a steep experience curve and enemies that require players to be at a specific level to survive fights with, whether it’s through a significant stat increase or a key spell that helps the player out. The notion that it’s well made comes from the fact that the developers tried to balance the game with precise increases in power at very specific points to reward and direct players, even though those who might have mastered the game to the point where they don’t die still run up against walls where they need to grind levels in order to progress. That said, as players gain power, even those walls can be overcome and things get easier with time. At level eighteen, it was still taking over three quarters of an hour to gain the four thousand experience points needed to gain a level, but at level twenty five, those four thousand points can be earned after only a half an hour.

The ending of Dragon Quest is notable in that, if the game’s intended plot is followed to the letter and players rescue Princess Gwaelin, it uses one of my least favourite aspects of a video game, a But Thou Must dialogue choice. When done right, it can bring a bit of levity to a game, especially when the game knows what the player is going to say and doesn’t pretend to give them a chance to choose otherwise, but when done wrong, it can annoy more than anything else. Case in point, Gwaelin asks earlier in the game if you love her and she won’t take no for an answer. At the end of the game, Gwaelin asks to travel with the player and also won’t take no. It doesn’t outright say that she wants to marry him, but future games imply that this happened.

The ending of Dragon Quest is notable in that, if the game’s intended plot is followed to the letter and players rescue Princess Gwaelin, it uses one of my least favourite aspects of a video game, a But Thou Must dialogue choice. When done right, it can bring a bit of levity to a game, especially when the game knows what the player is going to say and doesn’t pretend to give them a chance to choose otherwise, but when done wrong, it can annoy more than anything else. Case in point, Gwaelin asks earlier in the game if you love her and she won’t take no for an answer. At the end of the game, Gwaelin asks to travel with the player and also won’t take no. It doesn’t outright say that she wants to marry him, but future games imply that this happened.

This never sat right with me. First of all, I’m given the choice to turn her down and then I’m told that I must choose yes. The ending is basically being held hostage by a woman I barely know forcing herself on me. Second, I’d always wondered, what if the hero from the game is already married and set out to defeat the Dragonlord so that he and his wife may live in peace? It turns out that there’s an NPC who comments on the fact that the hero is wearing a ring and makes an insinuation that he’s not only married, but seems rather young to be married. Admittedly it could’ve merely been a reference to one of the pieces of equipment that can be worn by the warrior during the game, but it sure seems like there’s a really, really good reason to leave Gwaelin behind.

The reason the developers made this the ending is likely because this is wish fulfillment on the part of the player. A popular trope in medieval fantasy is the notion that the main character not only gets the girl, but the girl is in fact the princess of the entire kingdom. Often, he’s saved the princess during the course of the game or the book or the movie and has fallen in love as a result. But not everyone playing a game is doing so to experience these kinds of tropes. Getting the princess is nice, but saving the kingdom is better, and not everyone is willing to treat the princess as an object to be won. This is something that Squaresoft’s Final Fantasy series desperately needs to learn, as will be demonstrated over and over in the coming months.

I think the biggest reason why it’s always a princess (or some other feminine stand in for a princess) that is being kidnapped is because they are seen as weaker and easier to kidnap. Is this sexist? Perhaps. But an alternate way to look at it is that it’s not the developers being sexist, it’s the characters. Protagonists could have all the progressive views towards women, but must still spring to action whenever the damsel has found herself in distress. The damsel finds herself in distress usually because it’s a villain putting her in distress. The villains, after all, have regressive views towards women and are willing to treat them like objects to be fought for. The protagonist, therefore, has no choice but to play this game or else the safety of the woman is jeopardized. It’s all well and good to tell the villain that you refuse to treat someone like an object to be won, but your convictions mean nothing if the villain kills her when you refuse to rise to his bait.

I think the biggest reason why it’s always a princess (or some other feminine stand in for a princess) that is being kidnapped is because they are seen as weaker and easier to kidnap. Is this sexist? Perhaps. But an alternate way to look at it is that it’s not the developers being sexist, it’s the characters. Protagonists could have all the progressive views towards women, but must still spring to action whenever the damsel has found herself in distress. The damsel finds herself in distress usually because it’s a villain putting her in distress. The villains, after all, have regressive views towards women and are willing to treat them like objects to be fought for. The protagonist, therefore, has no choice but to play this game or else the safety of the woman is jeopardized. It’s all well and good to tell the villain that you refuse to treat someone like an object to be won, but your convictions mean nothing if the villain kills her when you refuse to rise to his bait.

It all comes down to a balancing act between Tropes Are Not Bad, the idea that tropes can be used well in a work, and All Tropes Can Be Overused, which is what happens when the same thing is used over and over again in a series to the detriment of more original writing. Damseling a princess, if done right, is an effective way to show what kind of evil your enemy is. It can make the conflict resonate on a more personal level. In Dragon Quest, the king pleads for you to return his daughter to him and to defeat the man who committed this crime. It is nothing as awful as when Kefka commits several acts of mass genocide in Final Fantasy VI, for example, but Dragon Quest is not meant to be that kind of game. On the flip side, Final Fantasy also begins with the rescue of a princess, and then nearly every subsequent Final Fantasy game features, at some point, the rescue of a princess or other such damsel. Although the circumstances each time make sense in the context of their stories, it points towards a lack of creativity in writing to continue to draw from the same well like that.

This is a subject that will likely be covered many times in articles written over the coming months.

The original Dragon Quest was the first of its kind, an RPG that captured the imagination and made players feel like they were a great hero, saving the land from the forces of darkness… by walking on the same patch of mountains and killing the same enemies for hours at a time. It might not be considered the best game by North American standards, but it scratched an itch in Japan and spawned an entire franchise, one which did eventually gradually tone down the grinding in favour of gameplay that was a bit more balanced. However, that’s a story for another time.

Next week, Squaresoft’s attempt at a Hail Mary throw establishes a second RPG juggernaut and helps to shape an entire industry.